Interview: Aaron Jasinski

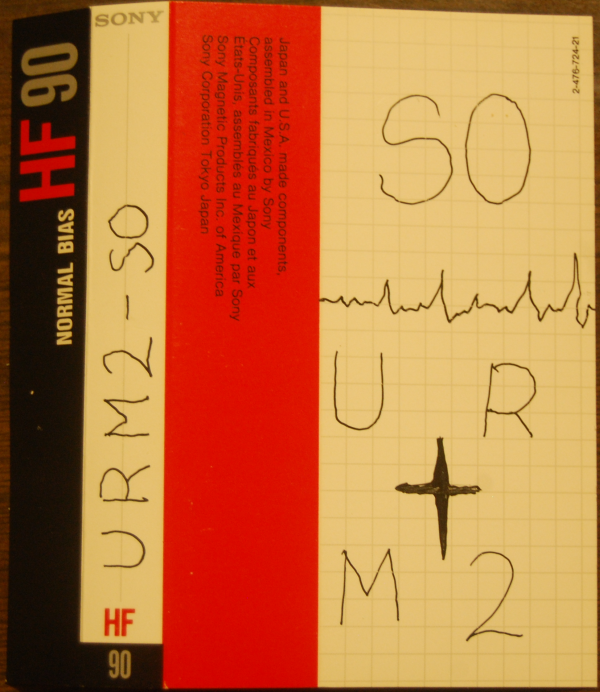

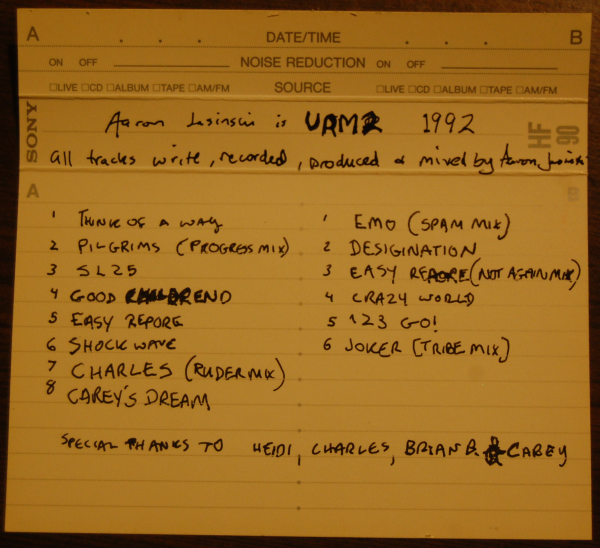

In the early 1990s I was just starting to review music and spent a good amount of time in random message forums talking to different folks, perhaps soliciting review copies of albums or demo tapes. One of the tapes that found its way into my collection was by URM2, called So. The J-Card was handwritten, the music actually went on longer than the cassette’s runtime, and it was clearly homemade, but the quality of the techno/electronica music on it kept me engaged and was something I’d return to even years later to listen to. Eventually, I made it a point to hunt down the artist thanks to the fact he put his name in the liner notes. At the end of 2016, we had a chance to talk.

Over the years I ran Normal Bias, I posted a number of homemade demos, but I believe this was the first time I posted a tape that was forgotten by the artist himself.

Ryan: I found it really interesting that when I first contacted you about this tape that you didn’t recognize the name that you’d released the tape under.

Aaron: Yeah, that was kind of a trip. I didn’t recognize the name. And subsequently to that first encounter I think I’ve remembered where that name came from. I don’t know if you were curious about that.

Ryan: That was my first question! Did the name of the band or the album (So) have any particular meaning?

Aaron: It’s really kind of dumb and nerdy. I don’t know about you, but my dad is really good at the dad jokes and maybe I kind of inherited that. It was from a like a little pun story that he told us.

He’s an orchestra teacher, and I was in his orchestra class. I played bass in the school orchestra in high school, and he told us this weird story that had a really bad pun ending about hillbillies or rednecks going out duck hunting, and he wrote those letters U-R-M-2 or C-M-Ducks. But he wrote out just the letters and he asked people to try to decipher it. And it tells this little story. And I think that’s where that part of that name comes from.

So the letters themselves make, spell out the words U-R-M-2. I don’t know if that even makes sense, but… I’m trying to remember like 24 years ago. I think that’s in whatever weird state that I was in at that time, I think I just pulled that out of somewhere.

Ryan: Right. Sometimes those things seem to come out of nowhere.

Aaron: Yeah, yeah. Or you connect the dots in a strange way and I was like, “Hey, that would be cool for the name of an album.”

I’ve been trying to think of how you got that tape. And the only thing that I can think of was, about that time, I was going to dance parties and really early days of techno raves and stuff. I think I had put that compilation together, or something like it, and was trying to shop it around to DJs, just to get people to play my stuff and I thought that would be really cool to have it played in a dance club.

And I think I put together a couple of packages like that. I was just trying to hand them out to people. That’s the only thing I can come up with and so I don’t know how it got to you that way. Or maybe I sent it off in the mail to somebody…? I dunno.

Ryan: The only thing I could think was that around that time was right around when I started reviewing music. Were you on any online services at the time? GEnie, perhaps?

Aaron: I think that was before I even knew what the internet was, I think. Maybe not. I think I might have sent it to some radio stations or something like that to try to get reviewed or something… so yeah, maybe somehow there’s some kind of connection.

Was that in the days of CompuServe and stuff?

Ryan: Yeah, I was using GEnie and I think I was using Usenet at the time. And I know that CompuServe had Usenet access so it’s possible, maybe that was where it came in.

Aaron: Yeah, I think my dad had CompuServe, or he had some really early form of the internet, and maybe I found something on there about, you know, get your music reviewed and sent it off or something, I don’t know.

Man, that’s like, that’s ancient history. That’s wild, that is wild.

Ryan: How old were you at time when you recorded this?

Aaron: I must have been 18, probably. Did it have a date on it? I don’t remember.

Ryan: It said 1992.

Aaron: 92? Yeah, so I would have been 18. Yep. Senior year or right after senior year. Probably like the summer of that year.

Ryan: When I got the tape, it was all hand-labeled. It had a little something drawn on the cover. It was somewhat stylized, but it was on the Sony J-card and everything. So, I got it and I was like, OK, what’s this? When I played it, honestly, I was surprised at how good the production value was for what I assumed was a homemade demo. What type of equipment did you record on? Where did you get the equipment? Was it something that you bought yourself or was it a gift?

Aaron: So that all started about… it probably was Christmas, or whatever. I was about 16 1/2 or maybe almost 17. And, well, to back up even before that, where did I get the equipment and stuff or how did I record it?

I’ve been fascinated by electronic music since pretty young, probably since nine or ten. My dad being a music teacher, he’s really into music and I remember him having this entire bookcase full of old LPs in the early 80s. He had a huge classical music collection, but he also had quite a few New Age type music, like Brian Eno, Tomita, who is a Japanese guy. I remember hearing Tomita’s version of The Planets, which is all made on modular synthesizers. And we’re talking like before MIDI or anything like that. I just remember being captivated in the concept of being able to create, what in my mind, seemed like any sound… just being able to create that on your own was just so awesome.

Fast forward to 16- or 17-years-old, I was really into electronic, like, synth pop type stuff, Depeche Mode and all that kind of music, and I learned that those guys used samplers and samplers to me seemed even more amazing, that you could just take any sound and then repurpose it and bend it and craft it into your own musical purposes. So I became obsessed with trying to get a sampler and samplers at that time were thousands of dollars, like the EMU samplers or Yamaha.

Then, I discovered the Ensoniq line of samplers, like the EPS-16+. That’s the one that I started just obsessing over, and I would just spend all day pining for this sampler. I was thinking, “How cool would it be to have a sequencer built in?” It came with effects and stuff. Basically, it was an early workstation. It cost like $2,000.

I tried to save up money and my parents, out of the goodness of their heart, said that if I got a job they would help me buy one. They would lend me the money to get it and then I could pay them back. So I ended up working at Taco Time for a year-and-a-half. After having the job for a few months they did go ahead and supported my obsession to get this workstation. And that is what I made music on, just that, for about three years, from 16- to almost 19-years-old.

So, the cassette you got was all done on an EPS-16+ from Ensoniq, recorded onto my dad’s Tascam dual cassette. It was a pretty nice piece of hi-fi equipment. It wasn’t professional, but it was pretty good for your home stereo system. I just adopted that and plugged it right into the outputs on the EPS and recorded it.

Ryan: I love that your parents waited for you to have been working there for a month or two just to make sure that you were actually gonna keep the job.

Aaron: Yeah, exactly. I think they wanted to make sure that I was committed. Maybe it’s just an artifact of my personality, but I remember just being sick. I had all the catalogs and had learned all the specs and everything and just being like, “Oh man, how amazing would that be to just be able to make… I’d have 16 tracks that I could put down and… it had two megabytes of memory and holy cow.” It was pretty awesome.

Ryan: And did it live up to those expectations once you actually got it?

Aaron: I gotta say it did. It was funny when I went into the music store to buy it, the guy was trying to get me to buy the Korg Wavestation, which had just come out at the time. The guy was trying to tell me that “Oh, you know, samplers are kind of a thing of the past, nobody really uses samplers anymore. That’s kind of a fad.” But I knew what I wanted and I think my perspective was proved right over all the years. Sampling is huge, right?

Ryan: Yeah, I would say so.

Aaron: I got to know that that platform super well. It probably kept me out of trouble, but it also severely cramped my social life. Being able to be able to sit in your bedroom, you’re like basically an early bedroom producer, headphones on… as I think you can tell from the music from that cassette, I was sampling TV and old movies and Monty Python and it all seems pretty cheesy now, but I remember at the time going, “Man, nobody’s doing stuff like this, this is cool!”

Ryan: Around that same time, I was just getting into doing sample-based hip-hop production, right about that same time, like ‘92, ‘93, just barely getting started. So, I definitely understand that those last couple years of high school, spending a lot of time with headphones on, and not necessarily out.

Aaron: Yeah.

So, production quality-wise, I come from a musical family and I loved music. As a teenager, I was exposed to quite a lot of different types of music and listened to a lot of music. I didn’t have the technical knowledge or vocabulary or understanding of how to produce things but I could hear the professional sound. I was constantly trying to get that and didn’t know why I couldn’t get to it but was doing what I could just through hearing, experimentation and just through listening. So maybe you picked up on some of that production value, but I didn’t even know what I was doing, you know? I didn’t have much theory behind it.

Ryan: Yeah, I mean, when I got it, like I said, I was really impressed by it. I remember still playing that in my dorm room a couple of years later. And I’m sure I probably even played it on one or two episodes of my college radio show at some point. So there you go, it did eventually pay off.

Aaron: It’s amazing, like, these little artifacts you create… it’s sent out into the world and unbeknownst to you, while you’re off doing other things, they’re having their own life. That’s just mind-blowing. Kind of creepy in a way, but I mean in a cool, sort of mystical kind of way.

Ryan: Yeah, I had a weird moment in the early 2000s, I had a guy contact me about sampling something I had produced back in college for a track he was doing. And I was like, first of all, “How did you get that? I sold like three tapes. So you must have been one of those three people that bought it.” And yeah, it is kind of weird to think that that stuff lives on and probably still exists in numerous people’s basements or the back of their closet or whatever.

Aaron: Right, that’s wild. Oh, man. Oh, that’s quite cool.

Ryan: So you had mentioned sending it out to radio stations and to clubs. Did anything ever come from it, aside from this interview?

Aaron: It’s all kind of murky. I remember taking some tapes of my work to various raves or dance clubs and trying to approach a DJ and say, “Hey man, I make music. Check out my stuff.” Some of them were too cool or kind of gave me the cold shoulder, but a few of them were like “Yeah, cool, I’ll check it out,” but no not directly. From that, nothing really came of it as far as getting notoriety or success or anything like that.

I mostly was making music at that time just for myself, really. I don’t think I even knew you could make a career out of it or how that would go. [I was] just kind of doing my own thing, because I enjoyed it.

Ryan: Do you remember if any of the songs on this particular tape stood out to you as a favorite?

Aaron: I don’t have copies of any of that stuff, which is too bad. I made a whole bunch more music, too, and I have no idea where all those cassettes went. But the stuff that you sent me, oh my gosh, I don’t even remember what it’s called now. But yeah, there are a few on there where listening to it, I recall making it. I remember designing the different instruments with the different patches and taking vocal samples and basically doing micro loops, shrinking them down to basically oscillators or sample-sized loops, and creating instruments out of those with filters applied on top.

I’m not saying I’m really cool, but people just didn’t do that really, I don’t think, at that time. Or like scrolling through a sample with a loop to create some weird effects.

And so hearing that, I was like, “Oh yeah, I remember doing that, setting up those sounds and stuff.” And definitely sampling some of the Monty Python stuff. I thought that was so cool at the time.

Ryan: Hey, it all worked in there, it made sense.

So… you thanked four people on this cassette. I don’t know if you looked at the J-card again or not, but were any of these people–and I’ll read you the names–were any of them special in any way? Like, did you end up marrying them or rooming with them at college?

You had: Heidi, Charles, Brian B, and Carey.

Aaron: How crazy.

OK, so, Heidi was one of my best friends from high school, and I think I’ve reconnected with her on Facebook, but we’ve kind of drifted apart. Charles was another good friend. I stay in contact with him once in a while.

[Brian B.] was a guy that I knew in high school that… we did theater, drama, together. If I recall, like, he liked my music, so I’d give him tapes and he would kind of give me his feedback. And then Carey was my girlfriend at the time.

And I didn’t marry any of the people on that list. I stay in contact with like two out of the four, thanks to Facebook.

Yeah, that’s crazy, yeah. So that had to be senior year. That was like, that was my senior year crowd, or right after senior year of high school.

Ryan: What other music or art have you have you made or produced since that time period?

Aaron: I’ve always been into art, like painting and stuff and music. My two mistresses, I guess you could say. And I decided to choose one as a profession and so I chose art, visual arts and stuff. I got a degree in illustration and I’ve had varying levels of success there. I currently work as a UI and graphic designer and artist for a small start-up, casual video game company.

I have done some music work, freelance type stuff for Microsoft. I’ve done some audio work for the company I work for, just on the side. I’ve won some remix contests, I guess you could say, in the music world. Mostly, I still make music kind of just for myself, just because I like it and the internet definitely has allowed for a platform that you can share that. So, you know, I put stuff up on SoundCloud.

But man, over the last 20 years there’s a lot of stuff I guess I could go into. Do you remember the mp3.com days?

Ryan: Oh yeah, yeah.

Aaron: Remember ‘99 and 2000? That was like a dream come true. You put up music, people listened to it, and you got paid. That was the coolest thing. I did that in college and made a decent chunk of money for just making music out of my bedroom. I actually met some pretty cool people that way that I still stay in contact with. That was the salad days of the internet back then.

Ryan: I think some of that stuff has started to pop back up on the Internet Archive. Remember the IUMA, the Internet Underground Music Archive? That might have even predated mp3.com by a little tiny bit. But I know that a lot of the stuff that had been on there has gotten pulled back up from the original servers or something up onto the Internet Archive. So you may have some more stuff up there that you may not know about.

Aaron: Oh, I’ll volunteer this. I probably should throw this in there because I think it’s kind of an interesting connecting link. One of my biggest, or most, I guess you could say, public successes in art, like my painting and stuff, was in working with the music artist BT. I did the album art for his [These] Hopeful Machines album. That was kind of a cool connection. I was commissioned by him and his record label to do the artwork. Simultaneously, I’m like, “Hey man, I make electronic music too!” Not that anything came of that, but it’s just kind of cool, the two interests of mine connected, and that album was really good.

Ryan: That’s good, yeah, you don’t want the one you do the album cover art for to be it a dud.

Aaron: I think he won a Grammy for that and the artwork was all over some iPod commercials. So, it was kind of cool to go, “Hey, well, that’s some of my artwork up there.” Personally, I thought that was kind of neat how some of my artwork was visible in the music world.

As this interview is finally being posted in 2025, you can find Aaron’s music on Spotify, Soundcloud, and Bandcamp. His art is at his website and on Deviantart.

I conducted this interview on December 16, 2016 for what was going to be the fourth episode of the Normal Bias podcast. Unfortunately, I never completed the episode. So, here we are in 2025 and I'm finally publishing the interview. If you like underground techno and electrionica from the early 90s, I encourage you to check out the tape we discuss, So, on the Internet Archive.

The interview is lightly edited for clarity. My end of the interview sounds kind of janky, mainly because I wasn't originally planning on my voice being in the episode.